Point of view

The (possible) importance of fashion photography

6 min read

Without question, photography plays a major role in global fashion culture and its industry and is commanding an increasing share of public consciousness. Our memory of fashion is really through fashion photography and its publishing, rather than fashion itself. But how willing are we to take it into a serious visual and cultural discourse – beyond its aesthetics and beauty?

Over the last few decades fashion images have engaged with new technology and proved politically and aesthetically provocative, economically useful, and ideologically powerful. But besides the massive amount of printed and online media on fashion photography circulating throughout our world, critical accounts of fashion photography are a lot harder to find. Photographic commentary has yet to contract with fashion photography in a much more sustained way and its perception of purpose and history hasn’t helped it gain status yet within cultural studies. Most often closely linked to its tying with commerce, its coquetry with the trivial and frivolous as well as its ephemeral character, fashion imagery still generally gets stuck in a narrow range of importance in cultural and visual contexts.

If we look at fashion photography in a more nuanced way, we should maybe ask the seemingly obvious yet impossible to answer question of how we define the genre of fashion photography and which responsibilities it can take on.

It would be wrong to examine fashion photography only through the eyes of advertisement or prettiness. It would overlook its ability to be a possible form of (self-) -expression, commentary on the world at large and/or reflection of time.

Our everyday lives are oversaturated with fashion images, magazines and blogs. The amount of fashion editorial production and publishing seems to now almost equal that of daily newspapers. Huge traffic and massive output leading to an overall opinion of fashion as mass media without any importance to add to the so-called »real« world? It really hasn’t gotten any easier to check the quality and importance of fashion photography as a serious form of possible expression and mirror of our culture.

On top of that, a fashion photograph and its importance are dependent on a whole network of influences. As Margaret Maynard argued in her essay »The Fashion Photograph: an ecology«, a fashion image is less a result of individual minds than a product of a variety of variables surrounding its production, publishing and consumerism. Maynard’s approach suggests that fashion photography and its relevance is best understood not in terms of the photographer as an author, or in terms of the fixed formal rules that constitute an established genre. It is much more a set of shifting practices without consistent rules or straightforward histories that are able to form and showcase its relevance.

In June 1945, the US version of Vogue magazine published a war photography series called »Believe it«, taken by the surrealist turned fashion photographer turned war correspondent Lee Miller* (the British version of Vogue had to publish different images of her war photographs due to reasons of propaganda). Miller’s coverage clearly of a documentary nature composed with the unique insight of an official war correspondent propelled Vogue into uncharted territory, far beyond its normal remit. As Anthony Penrose, Miller’s son, commented on this publishing decision decades later: »Vogue’s printing of Lee’s material represented an achievement in fashion publishing which has never been repeated.«

Willingly or not, American Vogue certainly respected Miller’s wish to picture victims and torturers, though by running her war photographs next to its fashion content, it obviously made them seem decontextualized.

Yet in a discussion on the relevance of fashion photography, in this example we should focus on Vogue’s role as a fashion publisher. On the one hand, the printing of Miller’s images and the juxtaposition of two seemingly strangely contrasting genres has raised ethical questions and the issue of trivializing history. On the other hand, a juxtaposed photo-reportage like this might be necessary, if not crucial, for a universal understanding of what is going on in the world at a given time. Don’t we need a view of the world at large that always includes both the good and the bad, the pretty and the ugly, the horror and the loving in order to understand it? If it matters, it matters. In the end, isn’t it every magazine’s job to take on the responsibility of its time – in fashion and beyond?

Miller and Vogue’s visual war coverage also clearly shows the idea that we should create and be constantly willing to re-envision and define the boundaries within which we work and live – and to adopt a certain fearlessness in our own lives and therefore our images and magazines.

»Vogue’s printing of Lee’s material represented an achievement in fashion publishing which has never been repeated.«

As a more recent example, Camilla Nickerson’s body of work as a fashion editor and stylist has been one of the most notable since the nineties for defining the moment and the undeniable link to its zeitgeist.

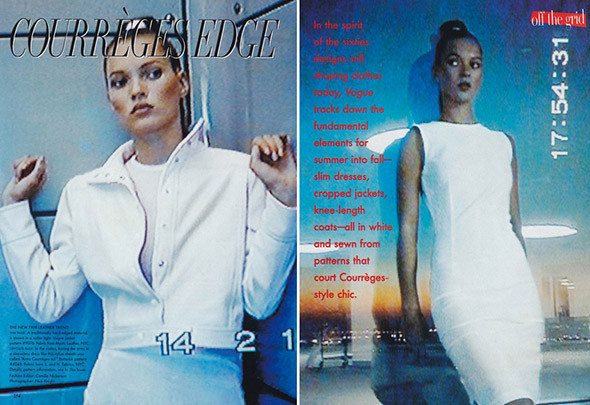

Whether it’s a transgressive Juergen Teller portrait or the unnerving sight of Kate Moss apparently captured by surveillance cameras in Nick Knight’s »Courrèges Edge« editorial (US Vogue, 1995), Nickerson’s photo stories are characteristic for their documentary effects in a field that is rarely concerned with realism. »Fashion can be a conduit for ideas, there’s always a message beyond (…), some kind of cultural comment. You might not be directly aware of it, but if it touches you, then something is being communicated. It’s incredibly difficult to convey magic in a photograph with such an influx of images all the time, but when it does work, it really stays with you«.

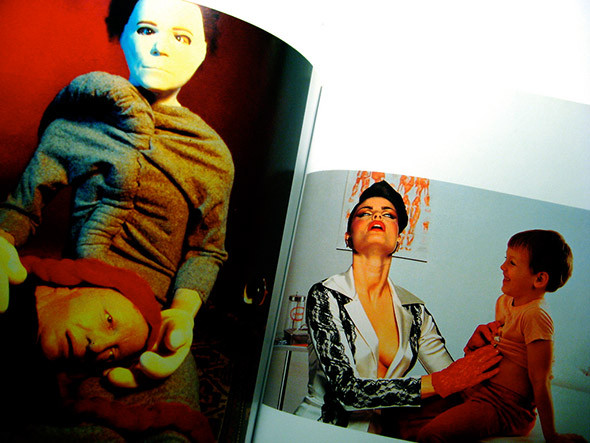

In 1996, Camilla captured the mood of the 90s in her and writer Neville Wakefield’s book »Fashion: Photography of the Nineties«. Its editorial strategy was to juxtapose fashion images with counterparts from the world of art and therefore display the influence of darker and more subversive ideas on styles of fashion photography in those years. Confrontational and often dystopian images by photographers such as Nan Goldin and Cindy Sherman were published alongside the work of David Sims and Steven Klein. It demonstrates the blurring lines of fashion photography and fine art (photography) and therefore deals with its ongoing issues of irrelevance and importance, triviality and value. Nickerson clearly shows throughout her images that fashion can clearly become documentary and documentary can clearly become fashion.

Understanding fashion photography as a serious medium of expression means to not only include a constant view and reflection on the world but to also certainly exclude our self-made boundaries within contemporary culture. Or in Nickerson’s words: »I’m always hoping (that on the day of the shooting) something happens and you just hope that it’ll fly. That it’ll become something that transcends time. That you will remember. You hope that it poses a question.«

* Martin-Gropius-Bau Berlin is showing a retrospective of Lee Miller’s oeuvre, including her work for Vogue, from 19 March until 12 June 2016.

By Inga Liningaan Langkay

You can find contemporary fashion photography from Previiew photographers and sylists in our Newsboard.

Exhibition

Harley Weir at FOAM, Amsterdam

London-born photographer Harley Weir, only 27 years old, has just scored her very first solo show at Amsterdam’s prestigious photography museum FOAM. But then that’s maybe not surprising for someone who shot a fashion editorial for Vice magazine at the tender age of 17 and has been the rising darling of the fashion world ever since.

READ MORE

Book review / Interview

Horst Diekgerdes

German-born Horst Diekgerdes is one of the country’s most renowned fashion photographers, whose obscure, surprising and surreal images have been part of iconic ad campaigns and major magazines alike, from Dazed & Confused and Vogue to Miu Miu and Hermès. He recently teamed up with Swiss art director Beda Achermann, a friend and long-time collaborator, to publish his very first retrospective monograph.

But what does anti really mean in a world where the word somehow already seems to have become so standardised?